A Universe Akilter

i.

“But you don’t love me.”

“What do you mean?”

“If you loved me, you ought to have greeted me with ‘miss Soli what a wonderful—take note of that word, wonderful—evening it is’ instead of a simple ‘hello.’ One can greet any acquaintance with a mere ‘hello.’ It is almost as bad as ignoring one altogether.”

“I don’t think that can be the case,” I tried to protest, but unfortunately the lady had already decided on her feelings and nothing would change them.

“I think you want me dead,” she proclaimed, in a loud, quavering voice; and all around her the ballpoint-pen eyes of her associates elongated toward us in mawkish interest. Behind feathers and fans, I could hear the trumpet-loud belch of gossip approaching. With every train-whistle shriek of the lady’s tirade—here is something like it, as far as I can recall:

Degenerate! Oh! Despicable! And not even washed your shoes! What reason did you have for leaving me that evening last June, when we were at the train station, waiting for the mail? Did the mail even arrive? No! not a bit! I have found certain letters in your own hand—oh yes, I’ve found them. Do you want to see?

Not letting a moment of my protest daunt her, she procured them: from out of her long furred parasol; reams and reams of the stuff all in brown ink, sludge-brown and beetled, as lame as an orange half-digested. “Explain. This.”

The utter silence was as curious and uncertain as a spider’s laugh, and quite as tenacious.

“I cannot,” I said, seeing the evidence before me. I stammered. “I cannot.”

“You see, you have treated me wrongfully. Take the damn things. Take them all!” She pushed them into my hands. Piled and dripping with the smell of overseas ash and heavy. They fell out of my paralyzed fingers, tracing circles around my shoes, which had been muddied from the rain last evening. On the way back from the opera, miss Soli had been in such fine spirits—it had been a flash of something brilliant in her that captivated me; and I can recall wondering if the hard times between us were over at last.

Still the papers were a complete mystery to me, for I had not written them. Yet it was without a doubt in my own hand, with my own name at the bottom, signing, dear, my love, little darling—to a lover I had never had!

The laughter began roiling. On every side, roiling, and the righteous fury of lady Soli made her face as red as a radiator painted red.

“Don’t! Not one word!” She turned to her fellows. “He says not one word in his defense! Have you ever seen such a reprobate? I feel wounded, utterly wounded—” her great black lashes clumped together as she blinked; her face shimmered with fat, blobby tears. They dotted the papers at my feet. They seemed to have enough force that I was not surprised when I gathered up the entire handful and edged out the door, because the salt of her tears repelled my hydrophobic spirit. But it was raining outside. The porch, a midden of a thing, stopped nothing. From the brim of my hat, the rainwater laughed at me, slipping over the words in my hand. I stuck everything in the pockets of my greatcoat until they were bulging open and I felt ill—sick and ill! The back of my throat was sour and scratched with sweetness. I walked out to catch a cab, and the mud slopped over my shoes. The laces were caked in mud. The sky was caked in a grime of smog and rain, stuck and cracked to the earth. By the time I had managed to pay the requisite amount, I was shivering, and I did not stop even as the heating turned up and great gusts of dry air blew into my eyes.

When one has just had a most public and humiliating rupture between one’s mistress and oneself—for reasons of a person of no existence—there is really nothing for it but to become familiarized with the crime. So having taken my things from our shared rooms to a hotel on the other part of town, I set all the letters upon the bed and tabletops and half-draped over the frowning face of the mini-fridge, and as they dried, timorously, I took off my coat and puddled it in a heap on the floor. I took off my shoes, and my socks which were grimed up to my ankles in an unpleasant arc, and my shirt, and my trousers, and my smallclothes, and my hat. Until at last, wearing nothing, I went into the bathroom to take a shower and found that the water was cold. Colder than the rain in fact, and so, staring into it, my spirit quailed. I couldn’t do it: step into that icy stream. It was more than I could bear. Instead I wrapped myself in a towel, still sweating and shivering and unclean, and returned to the relative emptiness of the hotel room.

The blinds were half-open. The chicken-colored light smeared its way through the fogstained glass. My toes shuddered on the miserable carpet. I had not eaten anything but hors d’ouvres at the gathering. I had been planning to make up for my lack of breakfast and lunch with lady Walstone’s famed dinner. But now my stomach rebuked me.

I sorted through the letters by date in order to read of the affair I had had.

It started last summer, or rather at that time when spring is ending and summer has just opened its arms in welcome. I can recall that at the time, miss Soli and I were staying at the Hotel Rip. It was when her interest in cello had just begun to fade, I recalled, and the music that had filled our speech became laced with silence. Still the air had been bountiful and I had never seen bluer skies. Every day, if one cycled down the path, one could look over a small stretch of white sand dunes into a glittering expanse, and there were crowds of tourists at every corner—ourselves part of the throng of that unwilling designation.

Little Sky, I saw you—I do not know who you are—standing on the edge of that small beach, pulling the sand with your toes. Your dress was chequered, blue as a print in a print shop. I would have tagged it a falsity but the sky behind you was exactly the same, as though in reproach. All morning I sat here, watching the dark feathered curl of your hair and creating bets as to the color of your eyes—I was quite partial to green, and had already composed sonnets in their honor, when you turned my way and I saw that they were brown. But the soft chocolate depths of them, with the barest glint of light when the sun caught the edges of that tilting moment between warm iris and the deep void of pupil, cast a tea-colored spark. I was entranced by the subtlety in those eyes, those ordinary eyes, and I decided I would write to you. There is no way you will ever read this, of course, for I will not send it, I will not get up and hand it to you—something so forward from a stranger—but merely remember your image, here, and this moment in which I saw something beyond perfection and imperfection.

Just as I read this, I recalled everything that I had written, but I knew that I had buried the letter in the sand, never to be found. Yet in its strange, formless, inexplicable way, I knew that she had answered me and written back, in a universe slightly akilter to this one.

I wished fervently that in some way I could read her letters as well, this nameless shameless girl, who lead a different me to start my next letter in such a manner:

You impudent creature. Of course we can never really understand anything from merely observing. Did I not just say that you were nothing but a figment? And a figment you would have remained, in my life, if you had not answered me as you did. You see? Now I must add to my basket of attributes about you: foul-tongue, sweet-breath, too-clever mind. You asked me what I would say to my description? You are right, right in every particular. I am obscene and vulgar, and I walked down to the beach in shoes. Actually I did not walk, I cycled, and thus the shoes. I didn’t know how I would be drawn onto that shifting uncertain surface until faced with it, that soft granular blanket in which sinking is the only thing that can ever be done. Without a moment’s thought, I stepped out as though I could float, but my shoes slipped, and ungainly, like a stick insect, I remembered my body. I remembered the limitations of all built things, and how shoes are meant for flat surfaces. Yet my pride had been set into a flame and I did not feel able to so easily take off my shoes. You might add to dangerous eccentric ‘a complete fool who overthinks the slightest things’ but perhaps you are already aware of this defect in my character.

My face, of course, is angular, and that is something I have had to live with. With a face like this, I could become either an artist or an investment banker. Every other opportunity is really a non-option.

But I think we were talking about you, my love—

What is the reason for that sidelong tunnel? For what reason did you plant lollipops in the sand? Do you ever get tired of building castles when the waves continually uproot you? Do not look for poetry in my reply, for I’m nothing but straightforward: the seaweed in your blouse disturbed me. It was worse than the mice listening to the band around the corner, which I saw you glance so disdainfully toward. If you are oil, then—?

This other version of me, whom I will henceforth refer to as the fool, was already leaping headlong into a tête-à-tête with our mysterious lover. Yet myself, I had picked up my pens, stuck my hands back into my pockets, and walked back up the long slope. I had picked up my bicycle and began skimming over the snap-pea clatter of cobbles taking me ever further from this mysterious her. I did not know what I was missing. I had no pang of regret in my heart, I did not glance back even once at that late-noonday sun and the black sharp shadows. The trees above whispered unfathomably, the red riots in them crowing, the marble top lawns falsely plastic shimmering. Then there was a light and I had to wait at the curb. The sweat on my skin dried as the wind of that rushing force paused, as I, the cyclist, was demoted to pedestrian, waiting in the heat, to be beset by flies. I waved my hand sharply and someone on the other corner glared at me, as though I had been gesturing rudely. The cool refreshment of water lay behind me in the ocean, the soft shadows of a bed in the villa, and in the town was the possibility for ratiocination. Ugh! What a bore, all of it (I had thought) full of my own artful ennui.

I should have done any one of those things, but instead I rolled into town and bought a newspaper, and cured my spirit’s malaise by depressing it with knowledge of the world’s spiraling futility.

This afternoon went to a funeral procession through town. There was much merriment and a few scattered flowers that had already gone rancid under our footsteps. After that, the ballet was a relief, though it was ungainly, with the heavy reverberations of their pounding steps, the wide sunwheel tulle skirts opening above those snaking legs. Your own amusements sound much more pleasant, all in all, and I do hope I shall one day be able to join you at the museum. I saw your drawing, lines growing softer in oscillations from the point of your utensil, as the folds the grit rubbed off into shadow upon shadow, and darkened my thumbs.

What a performance you have made of my face; putting some heavy strange mystery into the eyes that never existed. But we do that to each other, of course, being merely each others’ figments. Oh little Sky, what secrets have you threaded into the wrinkles of my jacket’s turned-up collar? What message are you sending to yourself the long way round? Is it narcissism after all, or is that only my reflection distracting me?

If I had your talent with charcoal I would add another, and that would be the birdsong angle of your wrist, reaching to tie the ribbon on your shoes. I only saw it once, and it was not such a pretty picture then, for your shoulders were sun-peeling and red and you had a tired annoyance in your rust-dust eyes as you tugged at the string. Away from the here and now, in memory, it becomes one of Degas’ ballerinas, something unselfconscious and echoingly real. But I know you have never danced, and I would not want you too. As I said before, there is such a heaviness to those movements, a falsity that is uncanny. Perhaps only we, with our careful manipulations, can pretend we are being as honest as it is possible to be.

Please, look in the mirror of your wash-bowl, chased with bluebells. Watch the dripping curls of your own dark hair, and find a picture within it, one that I would draw, if I could.

Such went the missive, and I could taste the lightness of that previous summer, though the drizzle had grown colder outside the single stale room. The bed was flat and pressed down, where I lay piled upon squelching towels. Alternating bands of light darted, spinning, through the low blinds, as car after car went past, lighting up the empty darkness in a somber tone, red light hollowing its way over the dip of my own angled nakedness. I shivered, and the blank ceiling was still, and the heater blew a pallid steam that barely reached my toes. Nothing but a candle remained on the table, and the papers, crumpled and drying, tossed with the scent of travel.

How ever did I fall from such a whimsical height, I wondered. In that nothing-matters-mood, everything was sensible, and there was no such thing as the slow, creeping embarrassment of my situation. If only I had truly written these things. Perhaps the me-that-had was now sitting somewhere else, safe under a blue sky.

The butterfly’s axial orb disturbs me.

Having spent now one full afternoon watching its frantic flutter back and forth from the spurn-tree, while S—— talked incessantly about her friends and the pallid unfortunate descriptions of the recent soirée, I have come to realize this. There is just something so darting and purposeful, and yet without admitting of the fact. Furthermore, it is full of movement, except when it is still, and hiding the colors of its wings by turns. I know you have drawn many things, and indeed the umbrellas of the café you sketched yesterday remind me of the folded wings of the butterfly; but an unreal version of it. Of course, once you put something to paper it is of necessity unreal. Nothing of the café remains in the two-toned umbrellas, just as nothing remains of the coffee and the kisses we shared brazenly as though we were there to be envied. But think on this: perhaps even the butterfly I watch is as unreal as my mind’s interpretation of the fact. Perhaps, under the sorbet sky and the soft sharp pinch of new shoes we are all, really, staring into space, seeing just what condenses best into our previous understanding, bisected occasionally by something resembling the truth, and which consequently scares us so much we turn right around and thenceforth avoid it.

I do understand what you mean about Galatea. The question remains—am I Pygmalion or Acis? Those two tales do have rather different drifts (and perhaps the life of a river spirit is no bad life after all, though one must be killed to do it—still, that does seem rather more your style. Which leads to my other potential: you are Galatea, sea-nymph, in spirit; moonlighting as Galatea the beloved crafted from stone. Which one would you rather associate with? (I have told you my preference, so we are fair). Of course there is still a certain self-focused arrogance to the casting. If drawing is more akin to carving, etcetera…

This is what I pondered during the endless luncheon; that is, when the butterfly let me rest, and that was only for fleeting moments. It darted this way and that way behind S——’s head in reproach, a mirror to my wandering thoughts, and consequently drew my attention to the fallen garters from the washing line that had lain itself over the blueberries.

What a strange difference I found, looking back at a version of myself that had never once existed, except indeterminately. For when I had watched the selfsame butterfly I had only felt the crushing weight of the minutes and an uncomfortable daydream about flinging the chocolate sauce into miss Soli’s face. Yet here went the fool on a lengthy tangent about mythology, likening his lover to the sea. If in fact she was the sea, I wondered at his recklessness in diving toward the waves, wondered, in fact, how it was that we had diverged in such a crucial respect: that he made mention, even in jest, of reinventing himself as a river spirit to join her.

It was a hard irony that seemed particularly pointed, what with the stiffened papers still damp along the edges, and the incessant rain outside my roaring door. With one hand upon the pile that had begun to form as I sorted the missives by date, I glared outside at the soddenness and the muck and the cold. It is one thing to be enamoured of the sea on a fine summer’s day and another to be drowned in icewater.

I left the papers behind for a time, got up and began fiddling with the disdainful coffee maker, shoving the packet open and spilling what hardly resembled beans so much as strong-smelling dust and waiting for the water to boil. The machine churned and stopped, churned and stopped, boiling at the slowest pace and wheezing in between as though finding the whole situation above its meagre abilities, and myself beneath its notice. Then when at last the coffee appeared, it was scalding and torturously tasteless, even filled with ripped packets of cream that I turned into novelty wastebuckets for the pet cricket I had never owned.

Smog. A blend of smoke and fog—a “fog” created of atmospheric pollutants. Something that crept slowly down the sodden streets and rose like an uncomfortably strong ocean. Inside the room, the gas-lamps’ wavering reflections did nothing for the uncertain yellow that pieced itself under the door and filled the entire space with a thick and tepid claustrophobia.

I took a sip of scalding coffee and regarded the room. In this saturated night, with the candle burned low, it was nothing more than an orbit, a cubit or a qubit of indeterminate size and shape. The dank paper smelled of mildew and soot; the windows were streaks behind the blinds, the bed, with its surfeit of pillows, was nothing but a galley moving ponderously through the dark. I had tried to avoid the sea, but the sea lapped in through the figmented, pigmented cracks between door and window, layered in air. I was still hungry, though the strong stench of the coffee that filled the room did something to assuage it. It was growing warmer, at least, and with a blanket thrown over my shoulder I absently picked up the next letter I had written, perusing it between sips of coffee that grew steadily cooler as my body warmed, the simple act of heat-transference one that reminded me of the impossibility of thinking one untouched by the world.

Interesting.

Dear little Sky, you always compel me to another perspective, yanking me backward from the precipice of the pool. As you say, there is no reason why both cannot be true; and indeed there may be some duality to all nature and all story. For if it were not for the binary sequence we would be stuck in place, and without two things to combine there would be no variations (shades in pigments; you see, I do know something about art.)

Actually I do know something about art; if only about the particulates of it. I, too, know of cochineal red, and the boiling of bugs preserved as something other than themselves, I know of snails and the royal purple stink. If colors come from mineral or biology, the answer is the same, each must be boiled down, must be unmade, to create something new; whether we ourselves were first living, or only breathed to life the moment brush was put to paper or waxed wood.

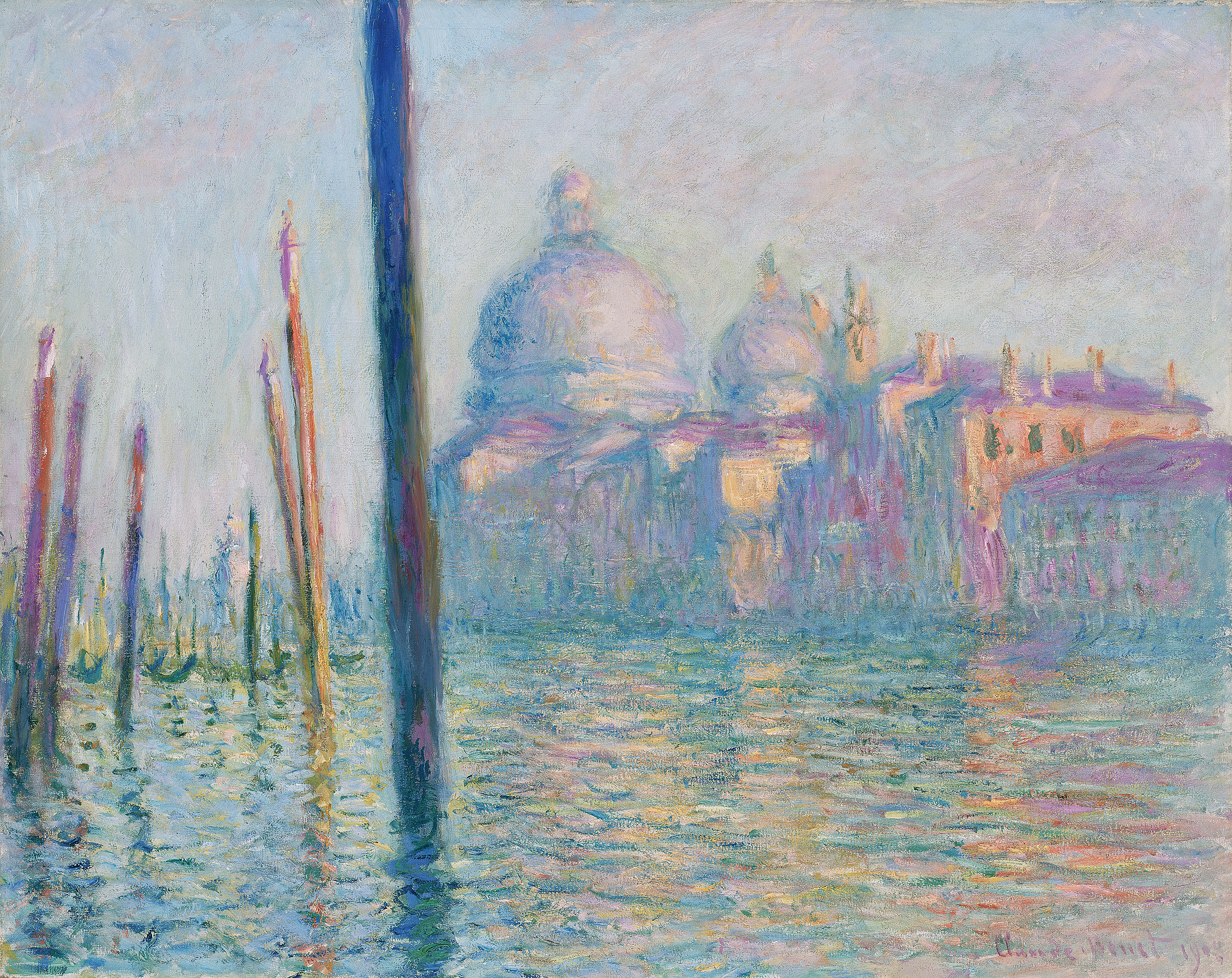

It’s a heavy subject matter, I know. I meant to talk of light things: sorbet, and linen, and décolletage. But when I think of light, now, even that turns the direction of my thoughts only toward the nature of uncertainty, of the movement of waves and the individuality of particulates. In this system of both, I dreamt of the sea.

I dreamt on the veranda, in the sun, under an umbrella, and the surf came crashing into my dreams with the grace of a rude elephant, or an errant ballerina. The lancets and lances went charging through the ordered predictability of my mind, and I woke up under a shadow, for the sun had gone during the course of my sleep, and the air was pregnant with rain.

I do fear for the future. Which of us does otherwise? Many times I have a way of ignoring it, and then it slides past me into the present, which will as soon become the past, and so I don’t let it alarm me. But sometimes, and only when I am talking with you, I wonder. If, indeed, this holiday ends—and it will… if, indeed summer ends and turns over, as it always does, to the sadly ponderous autumn, then will our minds, which will be full of different air, and our skin, which will be new, and even our brains, which will continue to keep time along with the electrical mechanisms of our ambiguous insides, so careful and messy all at once—if, in fact, time goes on, will you remember this fondly?

I don’t ask if you will remember me. That will happen, or it will not, as the world wills. I ask if you will remember this: this careful fearlessness, this wild hope. Keep it, if it suits you. If it is inappropriate to wear, among whatever society you find yourself in next, then tuck it near your breast as a favour, and consider it a gift beyond any words I might manage.

He truly was a fool, then; Love’s Fool. But the novelty had worn off, and something of the general hopelessness of existence had impressed itself upon him. Caked in melodrama, as usual, but he bared his sadly beating heart to the whims of the Capricious. There was an honesty on this page that almost unseated me, this something which had started as a lark, a sweet whim, an indiscretion to while away a deciduous summer. The other me, the Fool, had with every continuous word traveled further from the usual tracks of my own thoughts, until now it was less like looking into a wash-house mirror than a fun-house, and wondering at the strange distortions it implied. Like waves, certain parts expanded and contracted with each movement, until the head and all the limbs went jumbling together into a merry jig and lost all coherence, all semblance of the selfhood I prided myself on.

For the mind, which had opened itself to the sea, had begun to change its shape, as a coast does. Such a bewildering transformation had occurred in a universe akilter, while I meanwhile had dreamt of walking slowly to work in the morning, and finding that I had forgotten my hat.

My love,

There is always endless confusion, and endless irony. You, who now exist, will turn eventually into myth, or fade into obscurity. I say this not to be harsh but merely as a reminder of the capriciousness of fate. Even if you were to be renowned as the greatest painter of the age, like Zeuxis and Parrhasios, and could lure any passing viewer into your trompe-l'œil, the walls would fall eventually, and the paints and their pigments with it. But don’t think I brag that your monument shall be my gentle verse; for the truth of the matter is we are neither of us famous. (Don’t take my words to heart. Many times it goes the other way; perhaps I shall travel the paths of the future only as your strange muse, all my words forgotten in favor of your oil.)

I suspect it’s not the hope you were looking for. On a personal level, I find your art more than “charming;” it is wild and unaccountable, just as all art should be. Therefore put aside the words of your critic. What fools one will never fool another; and like the holographic photo at my aunt’s house, which shows its illusion only from one point, the effect depends upon what mind the painting is framed in—and each brings her own.

Locked in the stillborn gloom, I pressed at the edges of the water-stained paper with my fingers and thumbs until it crackled like the snap of ice. The mug was empty; only a soft stain remained. As I placed the letter down, and drew the blanket more firmly around my shoulders, I considered the Fool’s words. He was right, of course, about the fluidity of meaning. Furthermore, some may place secrets within their works, while others will stumble through just happy to have placed a few sentences into a coherent context, only to find that others have created an entire latticework of secret meaning. But, surely, I wondered, interpretability only goes so far. To go further would be to strike out onto one’s own adventure, breaking the mass of the art’s finished illusion. Truly, unless one wished to have utter control over the end-point and the meaning of the personal existence which was the work, and therefore denied it out of base fear, one would have to admit that piece inspires piece until what is left is a continual work of references made, understood and misunderstood, used and misused, bartered and stolen, written and rewritten and transformed; and that the work—all work—is a mutable thing, created by many, influenced by time and place.

A certain friend of miss Soli’s greatly disturbs me. It is not in the tubular protrusions of her jowls, nor yet the flounces of her Viennese skirts. It is not in her gait, which is ordinary, or her topic of choice, which tends to the banal, nor even her manner, which is as nondescript as to be almost insulting. It is, perhaps, something in her eyes—which have a certain way of judging—and perhaps also in the conversational turns she makes. You are, say, talking about the perennials, and quite soon you are suddenly realizing that this friend not only disparages any opinion you may have had on the subject, but doubts you have the perspicacity to come up with an honest opinion anyhow. If one really has no knowledge of perennials, it is only worse.

And nothing is more unnerving than having to see that individual at a garden party.

Perhaps it is in the very ordinariness of it all. For instance: if a tsunami were to suddenly pillage the coast, that would be a tragedy, no one would deny it. When gases of poison reach incrementally through the air, killing everything in its path, we all understand a wrong has been done, although we may have disagreements on the why or the how, or even the who. But the curious apathy, mixed with boredom, of the friend of miss Soli’s—that is truly terrifying. For it is the size of a great whale, and it hovers galomptuously under the surface of the grass and inside the flowerbeds and under the embroidered parasols, chased with marigolds, like slugs.

In the fact of such, one really wishes for a be-hatting—for all the hats to go flying away of their own volition into the air. Thus, in the face of absurdity, we could laugh; because it is the world in microcosm, but blown to a manageable proportion. But the miniscule vestments in which existence tends to travel is of a much greater impact, though small in scale. For you cannot quite pinpoint either the why, the where, the who, the how, or even, and most distressingly, the what.

A friend of a friend of miss Soli’s once threw a glass platter like a discus and it concussed an unfortunate gentleman with some force. It is still the talk of gossip today. But no one gossips about the way three cups were misaligned, and one without water; or how when a child was tucked into bed the blanket was forgotten, or the strange tenor of a hoarse voice trying to sing backward. And when I had finished visiting with twenty or thirty acquaintances of miss Soli’s and found myself unaccountably ill-at-ease with the entire apparatus, the entire machinery of existence, all turned inside-out and upside-down, I could not blame the parfait or the luncheon at four thirty-seven, or the choice of entertainment at the harpsichord or the fact that L——, a noted rival of mine in the business of plays, was in attendance. For there was nothing whatsoever to complain about. And yet—

Listen to me, I have still not gotten over it. The broken stem of a flower, and two small stones that fell down into my shoe. The undulating sea-serpent hiding under the grass, which is really no serpent at all. It would be presumptuous to call it existence, and more presumptuous to call it nature, and folly to call it society. What is it, then?

Is that, perhaps, what gives it the uncanny aspect? That it has no name?

This missive was just as I expected, although in my reality I had spoken of it to no one. I began to wonder, in fact, if this alternate version of events was really a sunnier plane, or merely the same one put through contortions. For if, even in the kindest mirror, all blemishes are still accounted for, then why should anyone wish to be on one side or another? True, the Fool had his Sky—I also had a sky, and one that was invading my room even now with its yellow-sea grit. I had called it a flight of fancy; yet the mire had followed, as soon as the floodgates were opened to truth, and the Fool opened his mouth to a creature kin enough to listen.

I am in similar difficulties. The title, at least, is quite clear to me—“Down in the Sungrove Garden.” At first I thought it would be about a small child, later I had fanciful images of straight-backed trunks going up to disk-like trees, and imagined it an orchard, where the lead would go during certain moments in and around instances of the confusion and depravity of the rest of the play. But when I sat down to write it, the only thing I came up with was this fragmentary dialogue.

B: I want you to think of someplace that makes you feel safe. Someplace warm, secret, quiet—a place you can just exist.

A: Something endless.

B: Is it?

A: Like a möbius strip. Endless and self-referential. It exists on its own.

B: Does anything exist on its own?

A: Of course not. But for the sake of the exercise…

B: Of course. I’m going to count down from ten, and when I get to one you’ll be there.

A: Down in the sungrove garden.

B: Exactly.

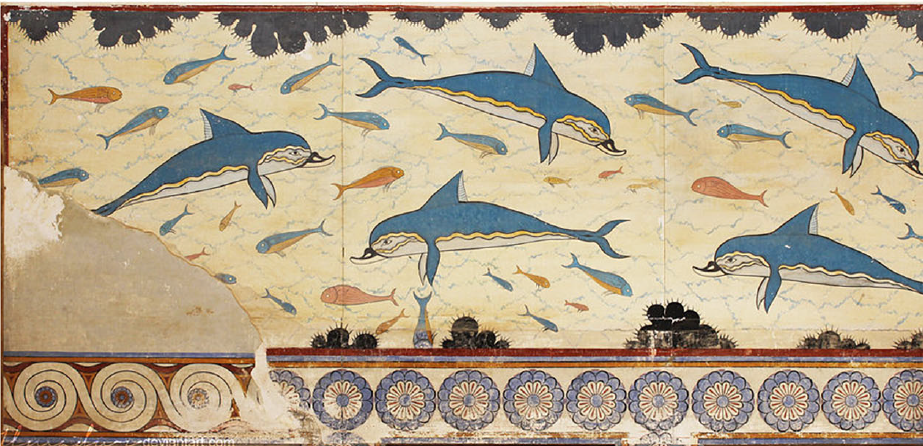

A: The disks are made of yellow gold. Very soft; when I touch it with my fingernails and press hard I can trace my own outlines into the causeway. No, it’s on a wall of course; an arch, a mural. Every time I see it I recreate it like an architect looking at ruins. I might create the fluidity of dolphins from a few crumbled pigments of rainbow…

B: And around you?

A: Yes, the trees. Each limb intertwined until I’m under a bower through which the light shines. It’s very soft; I hear birds and rustling animals. It’s all very perfect, very surreal. There’s nothing to disturb the image my mind has created. No buzzing flies or centipedes. No mud or sweat-sticky skin. It is almost like being in a museum, the way the temperature is always perfect—and we are in such silence. And, of course, the art made out of every unplanned piece. The cast of sun on the grass that reaches up to my elbows. It’s an illusion of course; almost like one of those holographic pictures at my aunt’s house. It only looks good from one point. But from that point, it lights up the way no painting could ever hope to recapture. I stare at it for hours but gain no insight. All I have is a memory I can turn into a string of words. An inadequate description, incapable of creating meaning between the bridge of our minds. Have you ever thought about the gulf?

B: Constantly.

A: And you don’t find it depressing?

B: I spend my time working, and remind myself that existentialism is as meaningless as any other human invention.

A: Very clever! I doubt it works.

B: No, but I turn my phone off every night and don’t check the news more than necessary.

A: There’s a river there.

B: What does it mean?

A: I haven’t the faintest. It sparkles like everything else; ripples each one over the other. Moving and never changing, changing and never the same.

B: Have you stepped into it?

A: And ruin my shoes? Of course not. No, I jest—but the truth is, if I step into the river once, will I be the same when I step out.

B: Or will it.

A: I knew we’d end up talking philosophy.

B: This is your mind. Your garden.

A: Perhaps. Sometimes I doubt it. Sometimes I doubt its perfection. And yet every time I retreat here I can believe that I’ll be okay. I can curl up on this concrete path, warmed by the sun, and stare through the patterned branches of the trees, and the green and gold and bronzish red of their leaves, and like the afternoons of my childhood time extends…

B: Why do you believe you’ll be okay?

A: Because I’m here, of course.

B: And at other times?

A: I have to contend with the world, which is, as we’ve established, not half so obliging. It’s selfish and terrifying… I don’t mean to insult existence. I really don’t. But there’s only so much I can take at once, so I filter my truth slantwise through the limbs of the trees.

B: Everyone does.

A: And some are convinced there is no truth. Perhaps they have a point, but it’s not exactly a solid foundation upon which to base action. I’m an optimist, you know. Assume there’s hope and act accordingly, and you may find yourself having succeeded. But if you think nothing is possible you’ll never try, and will spend your life in anger and misery to boot.

B: And does that fix anything?

A: Not a bit. Why else would I need this garden?

B: It sounds lovely.

A: I’d take you there, if I could.

B: If such a thing were possible.

A: If you touch the palm of your hand very gently and brush your fingers across it, that strange uncanny feeling is exactly what I’m trying to convey.

B: Uncanny? And yet your garden is perfect.

A: And perfection is uncanny. Or do you disagree? I’m not saying I don’t believe in the illusion, but if I took you there, I’d suddenly realize how much you’re not the thing I made you out to be. I’d start to think of how we never meet outside of this, and how I don’t know where you come from—or, conversely, how long you’ll remain in this world. Like all my other acquaintances, one day I may wake up to find you gone—dead, perhaps, or merely vanished, and I’ve never quite found the zen I need not to be terrified of that outcome.

B: You need to take more exercise.

A: Stop the thinking. Bridge the mind-body gap.

B: Even that’s an illusion, there’s only body.

A: Please; that’s an even more terrifying prospect. But I understand. I overthink. It’s something that happens when I talk to you; you oblige me.

B: Do you overthink, or do you merely spit out worn references, cobbled together with scotch tape?

A: I didn’t know we were talking about originality. I never claimed to have any.

The chief problem of which—I’m sure you can see quite plain—it will not entertain the masses, while for the avant-garde it will only seem trite. I retreated into self-reflexivity in order to stop the critique before it appeared (for then I can say, if one were to accuse it of being bland and monotonous, “that’s the point”—)

—but that is not the point, and we both know it.

Now you know. If this makes you feel any better about your own work, my dear, tell me, for this rubbish seems good for nothing else; it shall certainly never see the light of day. And yet I have to write something, or the world will think I am really nothing but a dilettante. (If I am, then that is a private matter.)

These letters were becoming less and less amusing to me as I read. And now, finding my own failure of a half-finished work thrown back in my face—“Down in the Sungrove Garden” being the only play I’d managed to continue last summer, in between the increasingly ill-advised jaunts with miss Soli and the ever-more-frequent trips to the café to brood—it was nothing but a mockery. I had consoled myself for some time, during those languorous afternoons, when I drifted about the summer-house peering through gauzy curtains, that if the play fell through I still had miss Soli, and that if the ardour between ourselves had cooled I at least still had her patronage. It was really for that reason that I had not broken things off at once, and—in a tryingly convoluted manner—the same reason I had not been able to write. For I consoled myself the other way as well, based upon whim—that if miss Soli were to tire of me, as it seemed likely she would, I would have, at least, a new masterpiece to unveil to the public. Instead, I had nothing but a collection of love-letters which could not even be salvaged as a poetic device and published as a bunch.

Yes, I considered it—pulling together these water-stained pieces of another life and trying to pass them off as my own genius. But it was worse than pointless. For not only did they lack titillation, they contained too much of my own maudlin thoughts, and to place them out for a penny for the public to look over would be a worse embarrassment than having to read them myself. In fact, I did not have to read them, and yet something compelled me to peruse the stack, some interest in what had changed and what was still running parallel, some morbid preoccupation with the Fool’s existence.

But I needed a break. I put the paper down, pulled my blanket even further about my shoulders, and went poking around the dingy room. There was an ice-box, sans ice; there was, of course, the bathroom with its cold water, and a great profusion of novelty soaps, there was the mirror which showed a wavering reflection, a pinched and tired face which seemed neither to have eaten nor slept. There was no miracle hiding among the folded towels or the rolls of toilet paper or the small tube of toothpaste. I turned on the water, again, hoping futilely that it would have warmed; but it was still nothing but ice minute after minute. I turned it back off, and watched the condensation drip down the tile.

There were no slippers, and my feet were cold.

I wandered back into the other room, closing the door.

I once read a book—I don’t remember the name—in which a woman did nothing but lie on the floor and consider making tea. It was a contrived set-piece, for a book, though as a play it would have been a tour-de-force. At the time I had chuckled at how contrived it was. For what would cause humanity, which of its own nature thronged together, to separate into pieces—and how long would such isolation really last?

All of a sudden I was struck with the knowledge that I needed to leave this claustrophobic room. And yet there would be no leaving while the air was still as thick as soup and as unbreathable. I was stuck here for the near future, and I had not even thought to bring a book, or entertainment, or even a few stolen éclairs. This severance from the world I had so derided was now foisted upon me.

With nothing else to turn to, I went again to the letters, and picked up the next.

Little darling,

I saw the first unarguable evidence of autumn today in the cut-back lavender. Every morning, when I strolled down the garden pathway to the village, it would entice me with its heady fragrance and bright purple profusion. Now those bending stems are gone, and the whole way seems emptier and more bare. There is something in the light, also, which has changed. I’m sure this was no surprise to you; you must have noticed much earlier than I, a holed-up creature, what with the way you dip your paintbrush into light in every piece you make.

I kept your last sketch, and—as you insisted it was only a scribble and folded it up yourself—have kept it in my wallet. This I looked at, today, when I ate alone, as though by paying homage to you in such a way I would increase your chances of success at the gallery. You will have to tell me what happened when you return.

I see something in your rendering I have never seen before—a sadness. Oh Sky, if I could take your sadness from you I would, though it makes for brilliant art. The shadows under the charcoal vase were deep, and the crumpled napkin, which lay underneath it, became a mountain range. I saw the corner of my own hand, somewhat blurred behind the glass.

There is never enough suffering, as far as the world is concerned, and we invent more on a whim; I wish that whomever invented yours would find that they always have only crumpled napkins wherever they are, and lukewarm water. It’s a paltry curse, as far as curses go, but if even once it makes you smile, I will consider it a complete success.

There was some irony in the Fool’s curse. Indeed, I thought it not beyond the pale to imagine that it was he who had caused both this continual wet gloom and the fact that the water ran nothing but ice. In fact, I may have exclaimed an audible “hah” upon reading that last letter, and it was with some resentment that I put it down and looked about the strewn bedclothes. But I found that, to my great surprise, in my engrossed perusal of the Fool’s journey, I had missed the fact that the pile of letters yet to read had grown slimmer and slimmer, and now, with the placing of this last one upon the careful, rippled stack, there was nothing else left.

But this was impossible! I still had no clue, yet, how the affair with the young Sky had ended, or if she’d gotten into the gallery as she should; in some way I had assumed that these letters would have followed the entire loop of my past, leading up to when I’d had them shoved so unceremoniously into my hand last night, amid the peering circle of gossipful watchers. To find the missives cut off so abruptly—and with neither explanation nor apology for the fact—disturbed me greatly.

It was with combined distress and resentment that I got up and paced the room, first in a whirl of thoughts, and then merely to move, though there was nowhere I could go as of yet. The candle was now only a stub, and the darkness was nearly complete, except for the light that muddily threw itself between the blinds.

In the corner, upon the desk, stood a pile of empty creamers, like a rubble of stones or a great and miniature ruins.

There was no sense in an end like this. Worse than the senselessness, there was no satisfaction in it, even of an unpleasant sort. There was just an empty gap.

But there was nothing that could be done. What had been written had been written on a different path, in a life not quite my own; and it was done with, for whatever reason. This I tried to tell myself, as I paced with ever more frustration upon the mealy carpet. I began to shiver, for the chill was real, and I’d left my blanket lying on the bed.

I cursed the Fool, and the Fool’s curse on me—and I cursed his ever-present inability to finish what he’d started, even in a bunch of letters chronicling a love-affair.

It seemed a sorry state indeed to be so cursed by a self that didn’t even exist.

I paused by the window—the air was still thick and soft and entire against the pane, so that it was nearly impossible to make out any detail beyond the wavering light. And at once the surety came upon me that if nothing else I would—if nothing else I must—break the Fool’s curse.

With this sudden purpose—I went into the bathroom, and checked again—the water was still cold. I stared down at the unrevealing porcelain as the few shivering droplets swirled down the drain.

Another way needed to be found.

So I put myself to the task. If the water would not heat itself, I would heat it.

I went back into the bedroom, filled the small coffeemaker with water, and stuck my empty mug underneath, plugging the whole contraption in. It boiled, in slow fits and starts, and then wheezed the water out in a great jumble of complaint.

The small mug in my hand was scalding hot, the water steaming and smelling still strongly of cheap coffee. I brought it into the bathroom, threw a towel into the tub and poured the water onto the towel, then filled the coffeemaker once again and stuck the mug underneath.

This I repeated, for at least ten repetitions, waiting with no small impatience in between, until the towel in the bathroom was soaked completely through. Finally, I stepped into the tub and picked up the sodden cloth, wrapping it around me. It quieted my shivers at once. I closed my eyes, feeling the water drip itself over my stomach, down my legs, pool itself at my feet; I brought the towel over my neck and scrubbed it across my hair, I covered my face with brilliant warmth and an odd coffee-esque perfume.

Then, the tiredness that I had not felt before descended upon me with sudden force.

I left the towel in the bathroom, dried myself with another, and returned quickly to the other room. I placed the letters upon the table and crawled under the covers, tucking them up to my chin. I therewith closed my eyes.

My dream came upon me as all dreams do: without beginning. I was wandering through the street-corner on a June evening, and beyond the low hunch of the station the shrieks of trains went by at convoluted intervals. Miss Soli was beside me, holding a feathered fan in one hand of an ostrich, and it moved the slow, hot air only slightly, providing momentary respite against the continual heat. We were soon to return; the holiday was over, and there was a careworn inevitability to every movement.

“Do stand still, would you?” she complained. “You’re giving me conniptions.”

I obliged, and leaned against the brick, but that didn’t help, for in another moment—

“And now you are tapping your feet. Why, what is this great impatience of yours? We’re only waiting for the mail, it’s hardly an excursion.”

“I’m only—”

“I know, I know,” miss Soli sighed ponderously. “Your artistic temperament. It hates stagnation. You’re too flighty to be held down. Something of the sort, yes?”

“…yes. Something of the sort.”

“Mm-hm.” She sighed again. “Why, I do believe the train is late. Can you imagine? And by nearly half an hour! Oh, there’s the station-master—perhaps he’ll know what the issue is.” She strode off in regal fashion, bearing down on the station-master with the full force of her intensity, and saying in a clear, clipped voice, “my dear sir—”

I took the first opportunity to slip away. Down past one geometric corner, where the sere grass was hiding, and over a low stone wall. I suddenly found myself behind the whole contraption, in that empty nothing-land which has not been prettied up. Following the back of the station for some time along the bare, windowless back wall, further than seemed plausible considering its small size from the front, I finally turned a sudden corner and found myself on the brink of the city.

The pyracantha were in a riot to the left, reddish berries bowing down with jeweled, smoky precision, and I knew there would be no passage in that direction, the thorns were too great. To the right, there she was, waiting at the appointed spot, as she had not been last time. I recalled her hastily-sent note:

Didn’t get in. It’s really a hopeless endeavor, I fear; this art of mine. I wanted to meet once more but the train comes early, and I have to go back to my family once it arrives. You know I have valued our little fling, far beyond what, I think, it has ever mattered to you. You believed in me continually, and I never knew how much it was that that lightened my steps enough to soar like the sky you named me.

She turned around, then, in surprise as I approached. “Oh!” she said, and a soft smile graced her features. “I didn’t think you’d arrive. It takes far longer to drive from the villa, and the times don’t line up any way I make my calculation—”

“In dreams, all things are possible,” I said portentously, and she raised her eyebrow in my direction. I grinned in awkward amusement.

“You sound like a coffee-mug,” Sky said matter-of-factly.

“Yes, it’s just because I’ve had it on me,” I explained. “The smell lingers.”

“I see,” she said, and leaned forward to discover if that was indeed the case. (It was, and we spend a few delightful moments taking the time to taste a sweeter indulgence; with a few swirling kisses pressed from tongue to tongue.)

Finally, it was she who leaned back, with a rueful sigh. “I didn’t regret our parting, but I regretted never having this last conversation, you know,” she admitted. “I still do; I go over it constantly in my lonely moments, imagining what you would have said if you were really here.”

“I know,” I said.

She reached down to pull a stocking that had begun to slip. It only sagged further, and with a distracted scowl, she plopped herself onto the dusty ground, hiking her skirts to her knees in order to tie the ribbon round it more securely.

Despite the humor of the situation, she seemed far older than I had recalled, in an indefinable way I could not express. It had nothing to do with her beauty; which was, as always, artless and sun-bronzed. It may have been her clothing, which was sensible travel stuff I had never before seen her wear. It might, also, have been the way that, when she tilted her head back and closed her eyes, a great weariness seemed to fall upon her.

Without another word, I sat beside her on that curb against the brick, that continual city stretching on before us into a haze of mist, the tangle of bushes separating us from the small town where we had met. There was a sense of endless expanse on every side but our own, and yet no way to get there.

On a sudden thought, I reached into the pocket of my coat—as thick and heavy as a winter coat, even in this heat—and pulled out the stack of yellowed papers, which I had read and sorted; the letters I had sent to her. “I noticed you lost these. You’re welcome to keep them—that is,” I stammered, suddenly blushing, “if you want to.”

She opened her eyes, then, and smiled again. Leaning forward, she took the papers and pressed them to her heart for one moment. “Thank you,” she said. “I had another drawing to give you, as well, but I left it outside of the dream. I’m sorry.”

“It doesn’t matter,” I assured her. “It was you I wanted to see, anyhow;” I said, and I brushed the fingers of one hand through her frizzed curls, and rested it against her cheek. Her solemn mahogany eyes, deep and reflective as an obsidian mirror, fluttered in and out of sight under the line of her lashes.

At last she said, “I was thinking, about what I told you once; of Galatea. I said I might as well be both, and I said it flippantly, but the thought has been turning over in my mind these past months. Sometimes when I move my arms under the cool afternoon shadow of a mausoleum, I feel everything like Galatea crafted from stone, and I know then that the inevitability of our parting was always fated. Other times, when the light shimmers against the glass, or I see the stream of water into a bowl filled with dandelions, and I place my hands inside against the grit, I know that I am instead a nymph, and that I will do anything to keep you with me. I am both. But not only that—for when recognize your face in the drawings I make, I know indeed that I am Pygmalion, creator of what seems most beautiful to me, finding through the lines I place what was already there in the paper’s emptiness. Other times, when my sadness is great, I know that I am Acis the lost, and it is you who transformed me into a creature of the waves. I am both, and I am all.

“And,” she continued, at last, slower, and her eyes traced their way across me as her lips spoke; “once I had realized that I came to recognize another thing. If I am all—so are you.”

“That seems,” I said at last, in a voice very wavering, and quiet, and deep, “exactly fitting.”

I awoke with the disorienting feeling that I had traveled a great distance; I recalled my dream with perfect clarity. Because I knew how these things faded without proper attention paid to them, I did not get up immediately, but caught, first, the precise reflection of Sky’s brown eyes in my mind, and the dusty place in between and beyond the rest of the world. Once I had that, I cast my thought over every part of the dream I could recall, starting from the train station and my wandering off, and went through the whole thing, paying close attention to every color, every building and unimaginable vista, every word spoken, not once, not twice, but three times entirely, until I was convinced it was as firmly in my memory as it was going to get.

At that point I allowed myself to take stock of my surroundings. The half-closed blinds let in a cheerful afternoon light, and the smog had finally lifted, leaving the air feeling clearer, lighter; as though a pall had gone from my very lungs. Even in this dry and stuffy room I could feel the difference.

All the detritus of last night was still laying about—my coat, in a sad heap on the floor, my clothes hung over the mini-fridge; the indubitable coffee-maker. And beside me on the table, right where I had left them, were the letters that had been given to me. I got up, re-dressed in my clothes from yesterday, which were still as grimy and unpleasant as ever, though at least they had almost dried in the night, now being only vaguely damp. I tidied up the room as best I could, and then picked up the letters in order to fold them and place them into the pockets of my greatcoat. But it was to my great surprise that, when I saw the topmost sheet, I knew quite at once that it was a letter I had not read before. A new one! And not written in my own hand, but Sky’s. Unimaginable!

Eagerly, I sat down to read.

Dear one,

You have always found me fearless. And I have never contradicted you on the matter, because something about your assumption of me was bolstering. You caught sight of me on the beach one day, on an afternoon where I walked disconsolately down to the ocean to find solace, for everything in my papers, and everything I drew in charcoal, recriminated me.

I did make fun of you, then, for you cut such a funny figure, ungainly wading through the sand in your shoes and your buttoned coat, looking as though you’d been waylaid on the way to some great party. But I made fun of you out of admiration, and I think you know that. At least, you smiled at me as if you did—not with the condescending turn I am all-too familiar with, but with something captivated. I saw you, glancing at me from the corner of your eye, while we both played coy and pretended not to notice the other’s gaze. I saw you take a sheet from your pocket and scribble something down, fold it carefully and place it with great ceremony into the sand, almost buried. I saw the sly mischievousness as you did so, and I recognized the invitation there.

Do you know, I almost turned away, then?

In a universe akilter, I might have—might have turned back and fled down the beach; pretended my afternoon had never been uprooted by such an event as it had been. I very well could have, and in fact I knew it—everything in me urged me to walk away, out of fear.

So when I say you have always found me fearless, I suppose I mean that you have found in me a fearlessness that comes and goes, like the tide. It was at a low ebb when we met. Even the bright sun did nothing to assuage my worries; even the knowledge that I had a whole summer here with nothing to do but tutor a sweet-tempered child in the mornings, giving her lessons in maths—

Well, you know all that, of course. I think you may have even seen her, once or twice, when we met outside the beautiful blue-and-white house, with its picturesque gables and its delicate lace curtains. She was very enamoured of you, in the abstract; for she knew full well we were involved in something full of mystery and intrigue, and would always sigh over the romance of it.

Ah, youth! ’Tis a funny thing. But I felt the same.

You made me feel the same.

It is for that reason that I feel as though I’ve done a great disservice to my own soul in avoiding you today, as though depriving us of a goodbye was anything akin to a kindness. It was cowardice, plain and simple, and I think I was aware of the fact even as I fled.

Now, without the rosy light of dawn and the fine sand of the beach, without the walks through the park every afternoon—will you recognize in me that weakness, and still see me the same?

I suppose it doesn’t matter if you do or not, for we aren’t to meet again; yet I wanted you to know. From where I write this at my desk, lamp turned low, in the depth and stillness of night, I find my mind chasing the memories of this past summer as though I might be able to grasp a thread within the shifting sand, something that I can sling this letter across. Perhaps it might reach you, then. Wherever you are.

I folded the letter, when I had read it, and placed it on the stack. I tucked the stack carefully into my pocket, turned around once more to survey the room, making sure I had not left anything behind—and then, with a strange lightness in my step, at odds with the preoccupation invading my thoughts—I left.

The city was already bustling, for I’d slept in late. I took myself over, first, to miss Soli’s apartment, where I began to pack everything of mine as well as I could; it fit easily into a carpetbag. I left her the key she’d given to me when we started our affair, on the counter where she’d not miss it. And then I made my way back to other lodgings, staying for a time with a few old friends of mine in what amounted to a gabled attic. Though it was small and drafty, it was rich in cheer, and continually filled with music and talk late into the night; always with one visitor or another and plenty of food that seemed to turn up in dribs and drabs, brought along by the innumerable visitors.

From this place, I took stock of my life, and bodies of work, of which they were all, unequivocally, a mess. “Down in the Sungrove Garden” was unsalvageable. Of other pieces in progress, I had some sketchy beginning of an operetta involving a haunted house and the adventures of a few siblings; a monologue about a small, inlaid box that was far too scattered to be any use to anyone, and a monograph upon the subject of perennials, which I had no desire to continue at all—a pity, for it was really the only one of the four that was of any quality.

And of course, there remained the letters between myself and my mysterious Sky.

I had thought the letter I found from her might be the last, but to my great interest, that was not the case; there were still a handful left, each one appearing at odd moments, always laying on top of the stack that remained. They did not come with any regularity; I recalled that she’d had many obligations that left her little time for anything but a few sketches here and there, and her letters—the memory became clearer as I read, and recalled those that had come before, that I had once had the pleasure of laying hands on not in this universe but another—had always been less frequent than my own.

The very next one from her started, in fact, in this way:

Dearest,

I took up drawing again, which I haven’t since June. Oh, no reason—I know you’ll ask and I plan to get ahead of you this time—merely busy, I suppose; and if you really want to know the truth, my inspiration has been flagging terribly since the incident last summer. I know, I know—you’ll tell me not to despair, and I do remind myself of it continually.

You may be aware—I had the feeling you were, though we never talked of it—but I did have a small success once. I was quite adept with watercolours of gardens, rivers, everyone having a wonderful time, you know, a real body of female work—and it was met with some acclaim. I still get mentions of it, now and again. My oils and everything else—the more realistically treated subjects—less so, and that is where my heart is taking me these days. Sometimes I sit down, telling myself sternly just to knock out a few peaceful images of what I’m already known for and it’s just a terrible tragedy, how stilted they become. I am afraid I’ve always been a slave to inspiration. I do envy you, really; writing is so much easier—you can cross out words you don’t like while I can only erase so much before the whole paper is worn through.

I like to imagine that when we parted—as if to balance out my own sad lack of progress—you’ve really finished one of those plays you always complained to me about. I think about you selling every copy in the run within five days. I know! A silly fantasy, but it does give me some pleasure. I am sure that the truth is much more mundane, but—I hope—still pleasant.

To that end, I write to you as though to a friend, for I know that even if we are no longer lovers you will always hold a particular space in my heart, us two being alike. If I’ve timed the dream right, if I’ve thrown this into the river at the spot where I should have—well, then you’ll get this letter, and if you do, I’ll know.

Don’t ask me how! But I am somehow convinced I will.

My sweet,

I am incredibly happy that you got my letter. It gives me more joy than you can think of, to know that this strange contrivance of mine has actually worked. And don’t feel bad for not writing back; it’s a one-way sort of thing, and there’s a lot of maths to be worked out in it, which you’ve told me yourself you can’t follow. I shall just imagine your responses, and if I get it wrong ninety percent of the time, well, I shall be content in never knowing!

It was the strangest thing, but I found myself pondering your play—the one you sent to me—in the letters from you that I lost, somehow, in the confusion of boarding the train. I remember much of it, and I even think I have the beginnings of an idea on how it might continue—though I have the feeling that I will not have worked it out before this parallelism between our universes comes undone again, and I am no longer able to send these to you. Because of that—because I know there’s not much time left—I sat down, during a free moment this afternoon, and really thought to myself what it was I wanted to say—what I would absolutely want to say to you if this was the last time we might speak. And, do you know, I was so delighted to realize that I think I’ve told you everything—

By which I mean, though it saddens me that this will soon be over, I am convinced you understand the most important things.

There is nothing, perhaps, that I really wish to say to you with such urgency, but I do have one last regret, and that is that I can’t send you my painting. It was inspired by the dream in which we met, and it won’t be done in time. But I wish desperately for you to have it.

Give me just a bit longer, and—if I can send you even one more letter—I promise, I’ll have figured it out.

Though it seemed unlikely, I did believe Sky’s promise. Though there were weeks, now, where nothing else appeared; and I knew she was correct that the strange alignment between our universes were fading. One afternoon I went out walking, hiding under an umbrella for the drizzle was chill and increasing. The park was quite near, and I picked up the pace, hurrying with a sudden knowledge that if I was to get to the river soon enough, I might see something uncanny.

Along the way, I’m afraid, I bumped into a young woman, and had to apologize profusely. She was wearing a veiled hat, and there was something about strangely familiar. In fact, I was just about to ask if we had by chance met before that—well—I still am not certain what happened. Perhaps I blinked; or turned my head at a sudden noise, or something of the sort; for in the next moment she had managed to walk away—somewhere down the wide street, which was empty enough that I could pick out every individual, and unless she’d gathered up her skirts and sprinted, well, it was rather unlikely for her to disappear so quickly.

I followed the road again and did make it to the park and the river at last; the river which was now frothing, fed by the rain. But nothing happened there; and quite soon, tired by the chill, I made my way back.

That evening, when I opened my desk-drawer as had become habit, I saw that there was one more letter; a very small one, this, taking up a few lines only of the sheet. I knew, without even reading it, that this was all she’d been able to send through, and I knew also that there would be no more letters; we had really drifted from each other’s orbits from the last time.

So it was with a certain amount of ceremony that I sat down by the desk, lit a candle, and read this message in the quiet evening, imagining her sitting at her own desk, toiling over what to say, her mouth a frown of concentration, her hair loose in her own chambers, her fingers smudged with paint and ink, as they always were under her gloves.

My Love!

I told you I would find a way round it. The painting is called “The Street Corner”— I’ve sent it to you in another dream; and though you might not remember the details, if you buy a pack of oils I think you’ll find that it’s in your fingers still, and will come forth without obstruction.

Yours always, through whatever distance,

Sky

I had no paints on me at the time, but I did as she instructed, and though I ruined a few canvases at first on trying to figure out the hang of the brushes and how to spread the stuff round, she was quite right that as soon as that was down I knew exactly what I had to create. It did come to me in a dream; though if it was a dream the night I got her last letter or another time I cannot now recall.

But that is how—in all honesty—I came up with the painting that is now the talk of the city. It was not my work at all, but another’s, and I rest humbly under her, my tutor.

It has taken some thinking, this past year; for that is how long this strange interaction between us has lasted. It has taken much thinking, in fact. I have considered the Fool—and I have considered how much I am, or could have been, he. If I was not, it was of the same cowardice that Sky admitted to herself, in honesty and in private.

But I am grateful to him, this other version of myself, for pulling me along this path, for without him I would never have met Sky. And—mayhap I am also grateful to myself. For I know indeed that if I had not taken steps to break his curse, I would never have been able to find the right dream at the right time.

Perhaps that is how all life is, though. A series of steps and missteps, chance and the seizing of it. If you, dear reader, have seen the painting—take another glance. For sometimes it’s the second look that matters most of all.

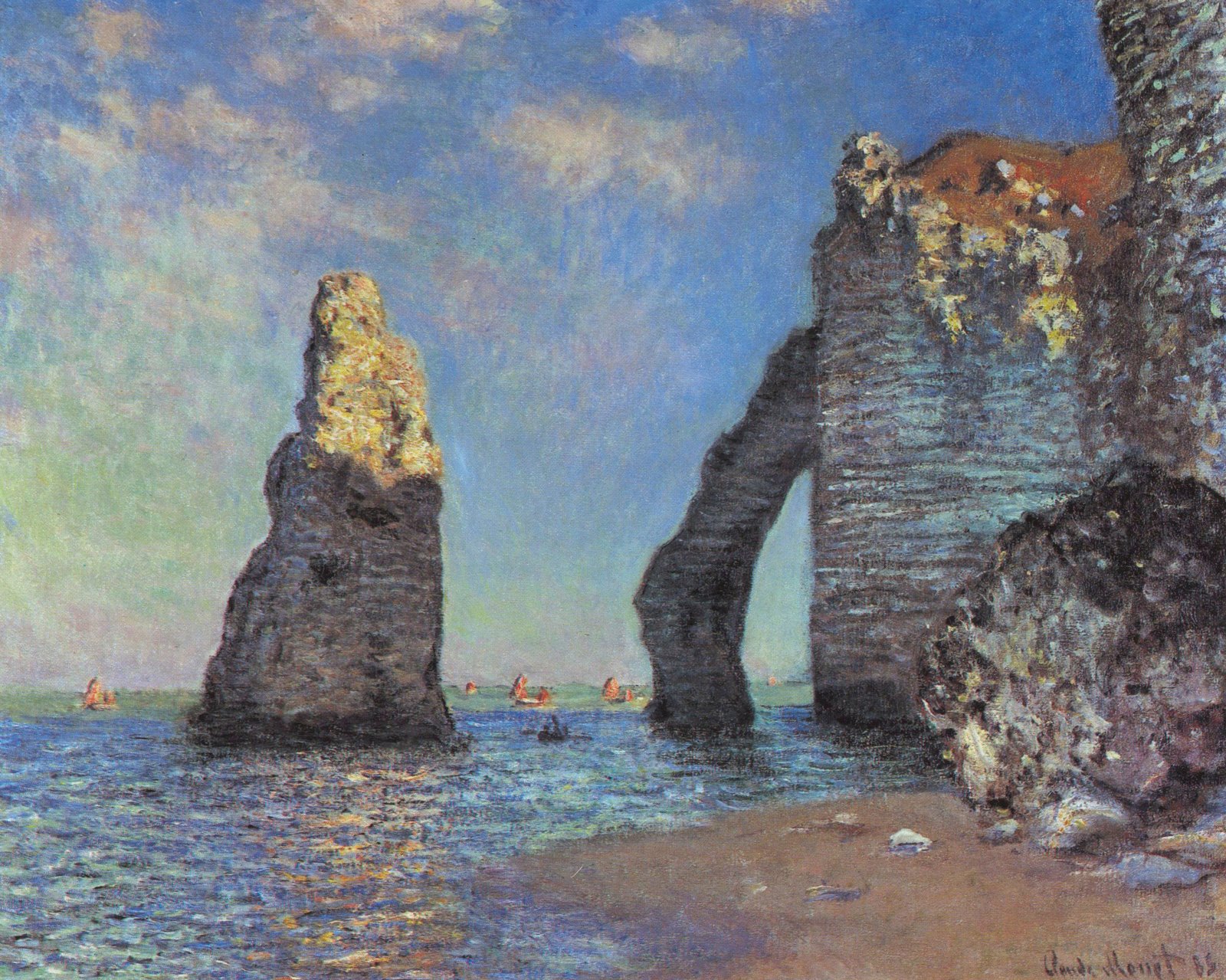

The bricks are grimed behind them, and their dark coats are old; the cuff of the slightly taller figure, where it rests upon a pile of letters, is worn. His head is tilted, and his hat obscures his expression; as her hat, with its lace-edged veil, does hers: there is the barest hint of nose and cheekbone turned up, and opened lips as though she is speaking.

There are many other figures in the painting. Pedestrians hurry by around them, carriages rattle in the distance, but in this one spot the movement seems to ease, and it is clear that both figures are fixed on each other, with a soft intensity of knowing.

It is a detailed, proportionate painting, done in shades mostly of brown and grey and dirty cream; only a few glints of blue hide in the wavering heavens, and the cobbles are chased with sludge. Still, everything shimmers from the recent rain: the dewdrops on the jackets and the umbrellas of passers-by, the shimmer of the water along the street; the few small windows, glinting like shards in the distance.

There is one puddle right below these two figures’ feet, and it seems possible they are even stepping in it; the way the shadows of their boots blend into the water below them. But—and here’s a secret—if you look close enough, you can just make out that the reflection in the puddle shows a clear, brilliant sky; and what seems to be the limbs of tall trees, glancing as bright as the liquid sun.